The tension between brand and performance marketing has become one of the major corporate issues of our times. That’s why we co-authored a feature article for the Harvard Business Review on how to address it.

The bottom line in that article is that brand and performance marketing could work better together by making the former more accountable for its financial contribution and the latter more accountable for its impact on brand equity. But after reading it, many CEOs and CMOs have asked us, “That’s great, but how do we know whether we have the right mix of brand and performance marketing?”

Business leaders are right to be concerned about this question because as we will see, getting the mix right can increase the revenue lift from marketing alone by as much as 20%! And for CEOs – who care as much about creating long-term value as they do about driving revenue growth – the impact on their company’s enterprise value can be as high as 14%!

In other words, having the right mix is worth a lot to the ROI of your marketing budget and its contribution to revenue and shareholder value. That’s why we’ve written this piece: to help you find the right mix for your brand.

BERA maintains multi-year data on the 4,000 most important brands in the world. The data include over 130 metrics on each brand, including four critical associations that comprise brand equity:

- Familiarity, the degree to which consumers feel they know and understand a brand, beyond just being aware of its existence

- Regard, how much consumers like and respect a brand

- Meaning, the relevance that consumers perceive a brand has to their lives

- Uniqueness, the differentiation that consumers see in a brand.

Together, these associations evoke powerful emotions toward a brand such as love, commitment, and respect or indifference, contempt, and even hate. Neuroeconomics tells us that such emotions account for over 90% of consumer decision-making. Thus, the best measure of “brand equity” is one that measures the drivers of these emotions: Familiarity, Regard, Meaning, and Uniqueness.

BERA customers use the data on these (and other) associations to implement the prescriptions in our HBR article and though not addressed in that article, they also use it to manage their brand and performance marketing mix.

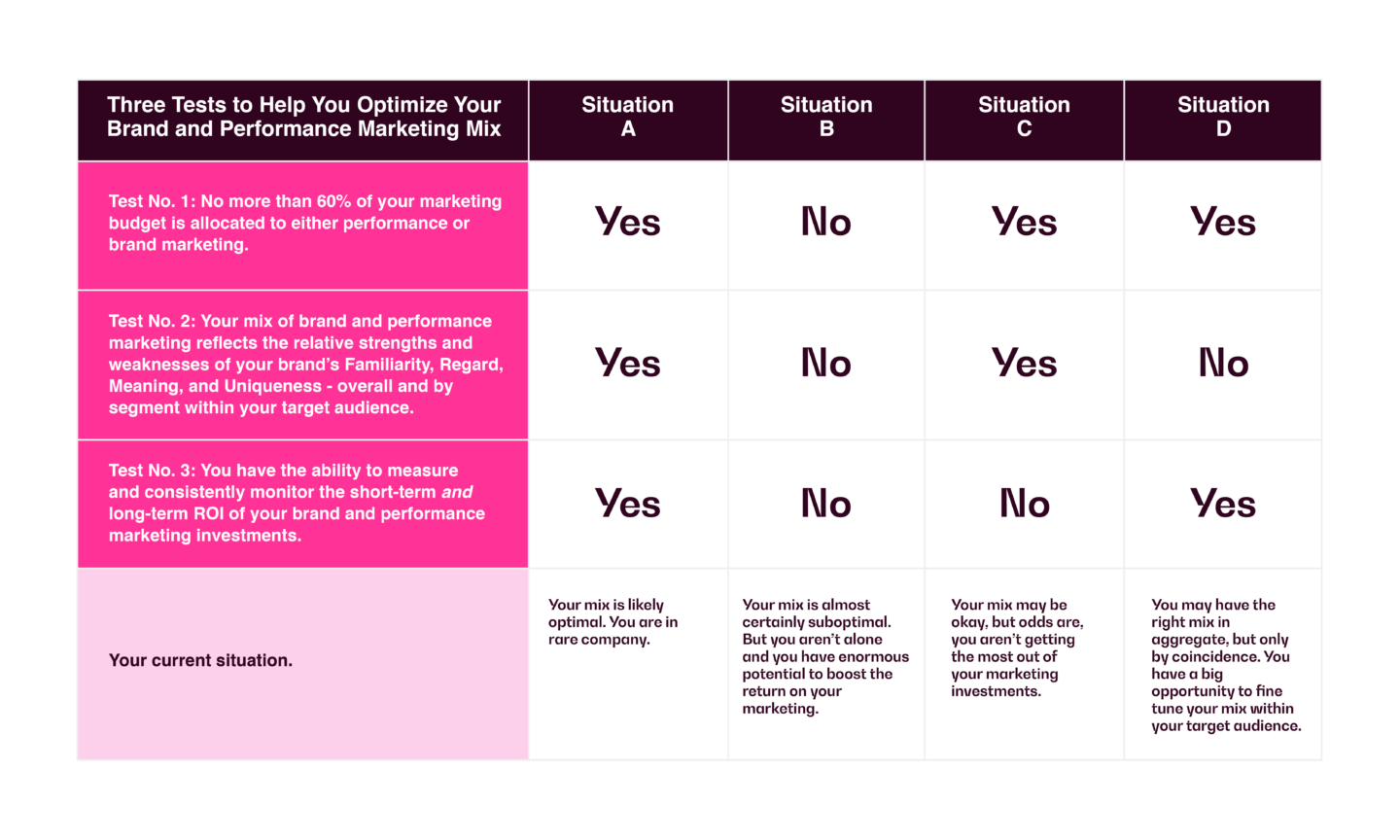

From this treasure trove of data and experience, BERA has developed a simple rubric that anyone can use to assess whether they have the right mix of spend on brand and performance marketing. It’s based on three tests:

- No more than 60% of your marketing budget is allocated to either performance or brand marketing.

- Your mix of brand and performance marketing reflects the relative strengths and weaknesses of your brand’s Familiarity, Regard, Meaning, and Uniqueness – overall and by segment within your target audience.

- You have the ability to measure and consistently monitor the short-term and long-term ROI of your brand and performance marketing investments.

As we will see, if you pass all three tests, you can be confident that you have the right mix of brand and marketing performance for your brand. That would be good news. But the even better news is that if you fail any one of the tests, you have a big opportunity to boost the ROI of your total marketing spend.

So, let’s explore each test to help you apply them for yourself.

As explained in the HBR article, brand equity growth impacts both current revenues and long-term value, brand marketing is particularly suited to growing brand equity, and performance marketing can affect brand equity even though its primary focus is to drive current sales. Thus, a mix that allows for either form of marketing – brand or performance – to exceed 60% of the marketing budget will be suboptimal with regards to driving current revenues, long-term value, and brand equity without compromising on any of them.

This test applies to almost every brand. But there are two exceptions:

Exception 1: super-small, highly differentiated brands with unaided awareness below 30%. They can use 90+% performance marketing because their imperative is to increase the number of consumers who have Familiarity with and Regard for what makes them Meaningful and Unique to their current customers, and to convert those consumers into new, loyal customers. Performance marketing is particularly good at this.

Exception 2: well-established brands with unaided awareness of 70% or more that have been essentially competed out of existence, such as K-Mart, Sears, and Chrysler. Brands like these need 90+% brand marketing because they are damaged goods and their Meaning and Uniqueness need to be revitalized.

Unless your brand qualifies as one of these two exceptions, no more than 60% of your marketing budget should be allocated to either performance or brand marketing. Otherwise, your mix is suboptimal.

This matters because it determines whether you should skew 60% brand marketing, 60% performance marketing, or somewhere in between. Here’s how:

Scenario 1: Your brand is in this scenario if it has high Familiarity and Regard with a broad audience, but its Meaning and Uniqueness has been lost over time. Examples include General Motors and Bud Light. For brands like these, brand marketing can do a much better job than performance marketing of revitalizing Meaning and Uniqueness in order to drive higher revenue volume and quality. Thus, their marketing budget should skew more 60/40 between brand and performance marketing, respectively.

Scenario 2: This is your brand’s scenario if it has high Meaning and Uniqueness with a relatively small group of consumers, but relatively lower Familiarity and Regard with a broader audience. This puts you into the camp that includes brands like Yeti and Tik Tok – lots of awareness with many people, but a lot of them don’t really know your brand all that well. Brands like these should flip the skew that is optimal for brands in Scenario 1, i.e., from 60/40 to 40/60. That’s because performance marketing is very effective at building Familiarity and Regard for brands that would have high Meaning and Uniqueness with a broader audience.

Scenario 3: If your brand ranks among the most loved brands on its Familiarity, Regard, Meaning, and Uniqueness, it’s in this scenario. This means you share rarified territory with brands like Apple, Bose, Duracell. Because of your high Meaning and Uniqueness, the context for high-return performance marketing is very rich for your brand. But – and this is a really important “but” – staying at the top of the brand mountain is a precarious position to be in. You need continuous investment to keep it there. Thus, for brands in this scenario, 50/50 is the optimal mix between performance and brand marketing, respectively.

Before we move on to the third and final question, we should note that your brand could occupy all three of these scenarios at once! How? Because the relationship consumers have with your brand may vary a lot by different types of consumers within your target audience. For example, your most loyal customers (“Loyals”) are loyal because they love your brand. For them, the optimal mix is defined by Scenario 3. With your customers who are “Switchers” – meaning, they promiscuously rotate between your brand and competitor brands typically based on who is offering the best deal at the moment – your brand likely falls into Scenario 2. And with consumers who aren’t yet customers, but open to becoming so, your brand probably occupies scenario 1. These “Prospects” already value your brand’s Meaning and Uniqueness – they just need a push to get them to convert.That’s where performance marketing can really shine.

All this means that your optimal allocation overall could depend on the right mix for each of the different segments within your target audience and the relative size of those segments. For example, a brand that has a high percentage of Switchers within their target audience should invest relatively more in brand marketing to build their differentiation and increase loyalty. A brand that has a lot of Prospects within their target audience should invest more in activation to convert them and capitalize on their interest in becoming a customer for your brand.

The impact on your marketing effectiveness depends a lot on whether the brand/performance mix is right for each segment within your brand’s target audience, not just the brand overall.

This test matters because the rules of thumb we describe above are based on the assumptions that your spend on brand and performance marketing is money well spent. All bets are off if your brand marketing is poorly conceived or if your performance marketing undermines your brand strategy, no matter how inadvertently.

To ensure the right mix, you need to be confident that the substance of your brand and performance marketing is solid. And the best way to do that is to measure and monitor their short-term and long-term ROI. By “short-term,” we mean the revenue (not just unit volume) growth that is attributable to a marketing investment relative to the cost of that investment; and by “long-term,” we mean the shareholder growth. To help you answer this third question, consider the following:

- What incremental investment is required to lift your brand equity by 1%?

- What is the revenue and shareholder value impact of increasing your brand equity by 1%?

- What impact do your performance marketing campaigns have on brand equity?

- What impact do your brand marketing campaigns have on brand equity?

If you can answer each of these questions with fact-driven confidence, you are indeed able to pass this third test. If not, it could only be by sheer coincidence that your brand and performance marketing investments – and therefore your mix of the two – are optimized for revenue and value ROI.

Other considerations

To be sure, there may be effects that would justify variation from the rules of thumb described above. These could be category-specific effects like those analyzed by Les Binet: online vs. offline, subscription vs series, and intensity/frequency of product innovation. Or special demand effects such as seasonality, political cycles, and one-off cultural moments. But these effects don’t really matter if you don’t pass all three of the tests described above and if you can pass them, your mix is already close to optimal.

Another consideration is whether you have the right level of marketing investment overall. If you fall short of – or exceed – the level of spend that is optimal for your brand and marketing ROI, the rules of thumb above need to be adjusted accordingly. All else equal, if you are chronically short on overall budget, you’d skew more toward brand marketing. As explained in our HBR article, this is because brand marketing impacts current demand and brand equity, both of which increase the ROI of performance marketing. This will help you get more bang from a lower allocation of your overly constrained budget to performance marketing.

If instead you are suffering from an embarrassment of excess marketing budget, you’d skew in the opposite direction – relatively more toward performance marketing. In this case, you have enough investment in brand marketing to get a sufficient return on the “excess” dollars going into performance marketing.

Putting it all together

To close, we provide the summary table below to help you diagnose where you stand today and what that means for the opportunity you have to optimize the mix of brand and performance marketing for your brand.

What to do now

This topic is a corporate issue because brand equity is a corporate asset and both brand and performance marketing impact it. As an extension of the CEO’s office, CMOs are best placed to be the steward of that asset.

Moreover, performance and brand marketing are different means to achieve the same objectives: revenue, value, and brand equity. Only the CMO can ensure that each makes it easier for the other to deliver on these objectives.

Finally, finding and maintaining the optimal mix of brand and performance marketing demands the right metrics and data to generate them.This may require adding new metrics and letting go of some current ones if they aren’t validated predictors of brand equity and its financial contribution. Only the CMO can make this happen.

The good news is that if you are in any one of situations B, C, and D in the table above, you have a gettable opportunity to take your marketing to a new level of effectiveness. Your first step is to convince your CMO of that.

Contact our co-author of the HBR article at kfavaro@bera.ai if you want to discuss your situation and how BERA can help you optimize your brand and performance marketing.